Conjoint Analysis is an analytic technique used in marketing that helps managers to determine the relative importance consumers attach to salient product attributes or the utilities the consumers attach to the levels of product or service attributes. Conjoint procedures attempt to assign values to the levels of each attribute so that the resulting utilities attached to the stimuli match as closely as possible. Like MDS, Conjoint Analysis relies on respondents subjective evaluations. [Read more…]

Marketing Research

Marketing Research

Multidimensional Scaling (MDS) for Marketing

Multidimensional Scaling (MDS) is a class of procedures for representing perceptions and preferences of respondents spatially by means of visual display. Perceived psychological relationships among stimuli are represented as geometric relationships among points in multidimensional space. These geometric representations are often called spacial maps. Multidimensional scaling are use for: [Read more…]

Cluster Analysis – a market segmentation procedure

Cluster Analysis in marketing is a process of grouping consumers of similar psychometric, demographic, geographic or socio-economic attributes into groups called clusters. The primary objective of cluster analysis is to classify objects into homogenous groups based on the set of variables considered. Marketers can use cluster analysis to segment the market and more effectively target the selected segments with relevant to them marketing campaigns. Cluster analysis examines an entire set of interdependent relationships and makes no distinction between dependent and independent variables. Independent relationships between the whole set of variables are examined. Cluster analysis is mainly used for:

- Market segmentation

- Examination of buying behaviour on a collective rather than individual basis.

- Brands in the same cluster usually compete more fiercely with each other. A brand can use cluster analysis for strategic positioning and to identify threats and opportunities on the market.

- With a set of homogeneous geographic clusters marketers can test their strategy on one cluster and if the strategy proves successful it can be expanded to all other clusters of similar characteristics.

- Cluster analysis can be used as a general data reduction tool to manage individual observations.

Simple example:

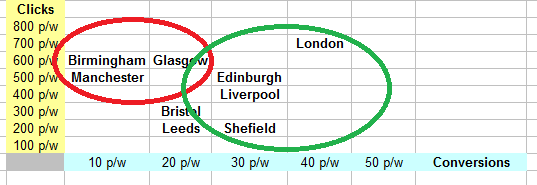

When optimising Google AdWords for our international shipping business we used cluster analysis as a campaign targeting tool. We wanted to reduce the cost of our Google advertising by putting all the large cities in the UK into two homogeneous clusters; the more and the less profitable one. The variables we used for the clustering procedure are:

- Number of paid clicks

- Number of conversions per click (CPC)

We identified from the cluster analysis that there are profitable and non-profitable groups of UK cities for our Google AdWords advertising. Birmingham, Glasgow and Manchester receive high number of clicks but relatively low number of conversions. On the other hand; Liverpool, Edinburgh, Sheffield and London receive higher number of conversions relative to the number of clicks. With this simple clustering procedure we know which geographic areas in the UK should be excluded from our AdWords campaign. The budget consumed by the unprofitable cities can now be allocated to the more profitable ones.

Nowadays cluster analysis is done using SPSS or MS Excel software but in order to understand this procedure properly one should know the mathematical logic behind it. For a simple demonstration of how cluster analysis can be done manually please watch this video:

Statistics associated with cluster analysis:

- Agglomeration schedule gives information on cases being combined at each stage of clustering.

- Cluster centroid is the mean value of all the variables or all the cases in particular cluster.

- Cluster membership indicates the cluster to which each case belongs.

- Dendrogram is a tree graph for displaying clustering results.

- Distances between cluster centres indicate how separate individual pairs of clusters are.

- The process of conducting Cluster Analysis

Formulating the problem is the most important part of the clustering procedure. Selecting one irrelevant variable may distort the clustering solution. Once you define the problem and select the right set of variables you now must select a distance between clusters or similarity measure. The most commonly used measure of similarity is the Euclidean Distance or its square. There are other methods also available and these are used for comparing the results and checking their validity.

Clustering procedure can be hierarchical where clustering is characterised by the development of a hierarchy or treelike structure. Agglomerative clustering starts with each object in a separate cluster and clusters are formed by grouping objects into bigger and bigger clusters. Divisive clustering on the other hand starts with all the objects grouped into a single cluster and clusters are then divided or split until each object is in a separate cluster. K-means clustering is a non-hierarchical clustering and is a procedure which first assigns or determines a cluster centre and then groups all the objects within a pre-specified threshold value together working out from the centre. Deciding on the number of clusters is usually based on theoretical or practical considerations. In hierarchical clustering the distances at which clusters are combined can be used as criteria. In non-hierarchical clustering the ratio of the total within group variance to between group variance can be plotted against the number of clusters.

Interpreting and profiling the clusters involves examining the cluster centroids. The centroids represent the mean values of the objects contained in the cluster on each of the variables. The centroids can be assigned with a name or label. To assess reliability and validity one has to perform cluster analysis on the same data using different distance measures and compare the results to determine stability of solutions. Splitting the data randomly into halves and performing clustering separately on each half and comparing cluster centroids across two sub-samples is one of my favourite ways. In hierarchical clustering the solution may depend on the order of cases in the dataset. To achieve the best results make multiple runs using different order of cases until the solution stabilises.

References:

- Tuk, M., 2012. Cluster Analysis, Marketing Analytics. Imperial College London, unpublished.

- Malhotra, K. N. and Birks, F.D., 2000. Marketing Research. An applied approach. European Edition. London: Pearson

Written by Michael Pawlicki

Choice Illusion – getting the prices right

How do the number of purchase options affect our buying process? According to the economic theory, more choice, due to preference matching, always has a positive effect on a buyer. Psychologically however, there is a choice conflict and choice overload. Too much is demotivating. The experiment in which I participated at Imperial College London provided evidence to support the idea that rather than facilitating our decision making process, having more products to chose from actively leads to choice fatigue.

One of the most fundamental techniques for display and pricing is known as the Attraction Effect. Products subject to sale become more or less attractive in the context of other superior or inferior products. Making a choice between two similar objects is hard.

The choice is easier to make when there is another product added to the choice list. The middle option is usually the winner.

By adding an inferior product to the list of choices available to the buyer we can facilitate the choice making process. The consumer perceives the products originally listed on the choice list as superior and finds choosing the right product easier. Junk options make the alternatives look good.

Compromise Effect – a set of three choices can be stretched upwards if the entire set is compared to another similar set with a salient end option.

————————————-

Formula for Choice Illusion:

Downward Stretch

1st Set: A B C

1st choice 2nd choice

2nd Set: E F G

Upward Stretch

References

- Maciejovsky, B., 2012. Choice Illusion, Consumer Behaviour. Imperial College London, unpublished.

Written by Michael Pawlicki

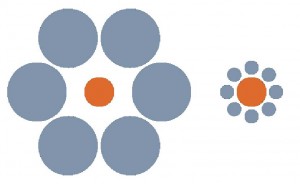

Ebbinghaus Illusion: controlling the perceived value

The Ebbinghaus Illusion is frequently used in TV and printed media advertising. DFS, a UK furniture store, was told by the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) to withdraw their advertisement from TV broadcast because of the false impression it gave to the viewers about the true size of a sofa. DFS, using green screen technology, manipulated the size of actors superimposed into the advertising video which made the sofas placed next to the actors look larger than they really were (BBC 2008). Interventions by ASA on the grounds of an illegitimate use of Ebbinghaus Illusion in advertising are rare. Generally, advertisers will get away with similarly blatant manipulation of product size for marketing purposes.

The use of the Ebbinghaus Illusion is not limited to marketing only. The value of money is subject to it too. The perceived value of money is determined by the comparison between the subject (money) and memory (anchor) or context in which a valuation takes place. Marketers can change the perceived value of money by influencing the context in which the valuation takes place. For example: A pair of jeans priced at £75 may seem expensive if sold in suburban areas of London. The same pair of jeans might seem cheap if found in shops in London’s Kensington.

Intertemporal Choice

Intertemporal pricing is the right pricing strategy for goods and services of high monetary value. This is due to people’s diminished ability to judge the true cost to them of purchase if payments for the purchase are spread across longer period of time. By multiplying the number of payments for the product over time, companies usually benefit from people’s reduced aptitude to compare the price they pay with alternatives. The notion of Intertemporal Choice has its roots in the Affect and Cognition branch of Psychology. Human minds are basically structured on two systems:

- Basic – spontaneous and rapid (animals and people)

- Rational – cognitive (only people)

So how does it work?

If we are already engaged in a cognitive process (thinking) at one moment in time, our ability to engage another cognitive process dedicated to another task is diminished. In a circumstance where we have to make two important decisions at once, our mind, in order to process those two decisions, will refer one to the basic system (spontaneous and rapid) and as a result the resulting decision is likely to be less rational. Marketers take advantage of Intertemporal Choice in involvement, affective and informational advertising.

Reference

- Maciejovsky, B., 2012. Ebbinghaus Illusion, Consumer Behaviour. Imperial College London, unpublished.

- BBC NEWS | Business | Advert banned for inflated sofas. 2008. BBC NEWS | Business | Advert banned for inflated sofas. [ONLINE] Available at: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/business/7762337.stm. [Accessed 12 November 2012].

Written by Michael Pawlicki

Pricing – Insufficient Adjustment Anchoring

This article concerns the underlying psychological factors business managers should consider when thinking about effective pricing. The definition of price this article will be working with is the following: Price of something is the total cost of adopting the product which includes purchase price, cost of switching, inconvenience and disposal. Each market segment can be characterised by dissimilar price sensitivity factors including: ratio between total and disposable income, level of involvement in purchase, ease of comparison, switching cost and perception of the market price of product (anchoring and heuristics).

The decision to buy, as far as the price of the product or service is concerned, depends on valuation. It is positive if the valuation a consumer makes of the good is greater than the actual price, and vice versa. Valuation is a cognitive process and consists of two underlying factors: Anchor and Insufficient Adjustment. Anchor is a piece of information (a reference price of the same or similar product) stored in person’s memory which is relevant to the item subject to valuation (a product). The process of valuation continues until adjustments fall within an implicit range of plausible values and this is an Insufficient Adjustment. (Epley and Gilovich, 2012).

Reference Pricing is a process of displaying the price of a product together with price of the same product sold elsewhere. A reference price is a kind of ‘artificial anchor’ where the seller facilitates the process of insufficient adjustment by subjecting the buyer to the anchor (in this case at the POS – point of sale). The routines in the process of buying are structured according to Heuristic. The human mind develops rules (software of the mind) which govern the processes of information processing when making decisions to buy. Marketers can blur proper functioning of Heuristics by using arbitrary and random numbers to distort valuations.

Most basic pricing methods are:

• Demand pricing – prices are altered or lowered according to the supply and demand for the product or service. The higher the demand the higher the price.

• Skimming – is the practice of starting with high price for the product than reducing it progressively as sales level off.

• Timing – is a procedure in pricing which helps managers predict repeat purchases. Marketers, mainly using CRM systems, can remind their customers about subscriptions. Here, the most obvious catch is if payments are disassociated from benefits the consumers gradually forget about them.

Reference

- Maciejovsky, B., 2012. Anchor and Insufficient Adjustment, Consumer Behaviour. Imperial College London, unpublished.

- Epley, N. and Gilovich, T., 2012. The Anchoring-and-Adjustment Heuristic. Why the Adjustments Are Insufficient. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.psych.cornell.edu/sec/pubPeople/tdg1/Epley&Gilo.06.pdf. [Accessed 10 November 2012].

Written by Michael Pawlicki

How concerned are you about your reputation online?

We asked Londoners how concerned are they about what is being said about them online and how does this affect their good name? The interviews took place in London in May 2012 as a part of the consumer research project for the Online Reputation Management.

Written by Michael Pawlicki

Influences – how other people make decisions for you

External influences are the key factors that influence people’s behaviour. The control of those factors, predominantly in the process of consumer decision making, is crucial for the achievement of any possible commercial objectives. The marketers can use the tools available to them to influence the Social Environment (all the behavioural inputs received from other people). Marketers should also understand the culture of their target markets.

Culture is a set of shared beliefs, attitudes and behaviours associated with large and distinct groups of people and this includes: religion, language, food and customs. According to Geert Hofstede culture can be defined and its strength measured by the analysis of the following factors:

- Individuals vs. Collectivism

- Level of Uncertainty Avoidance

- Level of Power Distance

- Masculinity vs. Femininity

In High Context Cultures where there is usually little room for personal expression or change and societies are more collectivist, conservative and sometimes even totalitarian, special marketing strategies are necessary. Inversely, Low Context Cultures are more individualistic and behaviours or consumption of products outside of well established standards is more likely to be socially accepted. Consumer Societies in Low Context Cultures are encouraged to be competitive rather than cooperative and are more likely to take risks to succeed (due to their general greed the next economic or social crises is likely originate from these cultures – exactly the same as in 2007). Consumer Culture is a creation of capitalism and members of the consumer culture are defined by what they consume rather than in what they believe. Subcultures are the best example of distinctive groups of people that share common cultural meanings and behaviours (UK’s baby boomers).

Using Social Class as a targeting tool is probably the most misleading and confusing technique in marketing (social class and personal wealth should not be confused here). Over the last few decades many people stepped up on the social class ladder without really increasing their personal wealth. Targeting low priced products at lower social classes is a common marketing error. Some marketers assume the lower social classes consider the price of a product as the only purchase decision making factor. The Trickle-Down Theory implies that lower social classes often imitate upper classes by consuming products marketed as products targeted at higher market segments.

UK’s social classes are subdivided into five categories.

- A – Upper-middle class

- B – Middle class

- C – Lower-middle class

- D – Working class

- E – Lowest level of subsistence

Peer and Reference Groups – humans are social animals. A reference group is a person or group of people that significantly influence an individual’s behaviour. People often buy products or services not because these are necessary for their existence but as a means of communication to their peers. The choice of product will depend on at which group the intended message is targeted at? Most common reference groups are:

- Primary Groups are usually friends and family and can be characterised by face-to-face interaction on a regular basis.

- Secondary groups are people who we see occasionally and with whom we share interest but this group in comparison to family is usually less influential.

- Aspirational Group are the groups an individual wants to join. Very powerful in influencing behaviour.

- Dis-associative groups – groups the individual does not want to be associated with.

- Automatic Group – gender, age etc

The process of learning which behaviours are acceptable within a particular group is called socialisation. As a result of contact between an individual and a group the relationship may either turn into:

- Conformity – change of beliefs or actions based on group pressures.

- Compliance – individual goes along with the group without accepting its beliefs.

- Acceptance – individual accepts behaviours and shares group’s beliefs.

- Normative Compliance – the pressure on an individual to conform and comply. The source of normative compliance lies in operant conditioning (very powerful).

- Homophilious Influences – transmission between those of similar age, education, social class etc.

As far as the entire life of an individual is concerned family is the most powerful reference group. Family and individual have face-to-face contact, share consumption, subordinate their individual needs, select family purchasing agents and usually nominate one as a dominant member of the family.

First born babies on average generate more economic impact on families. This is because the first born babies require parents to buy all the necessary care products for the first time. Parents often learn how to care for their children through a system of trial and error by buying and using care products for their first child and use this knowledge to save money when caring for their second child. Children, on the other hand, use their Pester Power to exert pressure on their parents to buy something for them. Young teens in high income economies in particular have more influence on family because they watch more TV. Often they accompany the purchasing agent shopping and their purchase decision making process is heavily influenced by TV and Internet marketing.

Parents can be characterised as:

- Authoritarian – cold and restrictive

- Authoritative – warm and restrictive

- Permissive – warm and non-restrictive

- Strict Dependent – fosters dependence

- Indulgent Dependence – giving everything the child wants

Rituals are the occasions when people spend money for irrational reasons, sometimes even more money than for any other reason. Examples of ritual purchasing are:

- Exchange Ritual – gift giving

- Possession Ritual – photographs of beautiful cars

- Grooming Ritual – preparing oneself for public

- Divestment Ritual – cleaning, redecorating

References

- Maciejovsky, B., 2012. External Influences, Consumer Behaviour. Imperial College London, unpublished.

Written by Michael Pawlicki

Classical Conditioning Examples – what can customers learn from you?

One has learned something if, as a result of an experience or more information being made known to them, their behaviour changes. Learning is a process of behavioural changes that occur over time relative to an external stimulus condition.

The definition of Pavlov’s Classical Conditioning is: “Unconditioned stimulus leads to unconditional response”. What it means in practice is that certain kinds of acts lead us to conduct another act as a rule e.g. smoking cigarettes may tempt the smoker to drink a cup of coffee. In marketing, classical conditioning is often used with sounds to accompany advertisements. Consumers, by hearing the sound, are reminded of the message they saw in the advertisement. Additionally, liking the sound extends to liking the product subject to advertisement. The repetition of sound (unconditioned stimulus) is key in order for classical conditioning to be effective. The number of repetitions required depends on the strength of stimulus and the motivation of the individual. Classical conditioning is involuntary. Individuals are not required to actively participate in learning.

Generalisation – stimulus that is close to an existing/known one evokes the same/similar response.

Cognitive learning – is learning through conscious analyses of purchase. The emphasis is on what is learned, not how it is learned. Cognitive learning consists of:

Cognitive effort – Cognitive structure – Analysis – Elaboration – Memory

Memory – is the mechanism by which learned information is stored.

Sensory memory – (Attention) – Short Term Memory – (Elaboration) – Long Term Memory

Operant Conditioning by B. F. Skinner – takes place when the learner conducts trial and error behaviour to obtain reward and avoid punishment. The learner has a choice of outcome of their behaviour and the process of trial and error involves cognitive dimension (thinking). In marketing, Operant Conditioning is an idea that is highly relevant to industries that rely on repeat purchase, particularity for FMCG (fast moving consumer goods). If the first time a purchase is made has had a positive effect on a consumer then they are positively reinforced. For example: if a consumer buys an ice cream and is satisfied with its taste and quality (reward), the same consumer is likely to buy the same ice cream in the future in order avoid disappointment from buying an ice cream of unsatisfactory quality (punishment). The main difference between Classical Conditioning and Operant Conditioning is that the former is based on voluntary behaviour, and the latter is based on reflex.

Knowledge – the more one knows about the product the lower the perceived risk is.

- Consumer knowledge consists of:

- Self Knowledge

- Knowledge of brands

- Consumption Knowledge

- Persuasion Knowledge

Reference

- Maciejovsky, B., 2012. Learning, Consumer Behaviour. Imperial College London, unpublished.

Written by Michael Pawlicki

Maslow Hierarchy of Needs for Marketing

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs does not require long introduction. It is in my opinion one of the most important marketing concepts ever invented. In this article I update Maslow’s theory slightly to make it more relevant realities of modern European. Entrepreneurs and investors, before investing their time and money into new ventures, should test their ideas against this and how well their new business would measure up when assessed using Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

Survival Needs – used to be about covering one’s body to protect it against cold and having access to food to survive. Today, survival needs are more to do with fashion, healthy living and conspicuous consumption. As marketers we should think of human’s survival needs as an opportunity to deliver demanded and differentiated clothing and food products to the market by the means of mass customisation and co-creation.

Security Needs – The most obvious examples of products and services which directly appeal to a human’s security needs are insurance, saving plans, burglar alarms, car breakdown memberships and computer anti-virus software. The less obvious are the things like dating sites. In uncertain economic times in particular, some dating websites site may choose to position themselves as sites which help their users to develop true and long lasting relationships. By doing so they purport to increase the social security of both members of this newly developed relationship.

Belonging Needs – Products and services designed to appeal to the need to belong are probably the most profitable ones. The motives behind their purchase are mainly irrational. People are willing to pay dearly for fashion products in high-value categories, luxury goods and club memberships not only to benefit from receiving the service it provides but to belong to a group of people of similar socioeconomic characteristics. Europe, with its demographic imbalance between senior and junior citizens, presents a great opportunity for marketers capable of addressing the need to belong in the form of offering vintage products to those born just after WWII. By owning a product such as a classic car people can reach back to the time of their youth and meet and chat to other people of the same generation and interests.

Esteem Needs – Are often confused with the need to belong. The two are actually quite opposite. The need for self-esteem is often fulfilled by the ownership of rare and unique products such as an expensive house, jewellery or car and nearly everything which implies one’s social status. The uniqueness, rarity and individualism that are presented throughout the process of fulfilling one’s esteem needs, will unfortunately often prevent an individual from belonging to a certain desired group of people. Rolls Royce is a good example for this. The products addressing esteem needs require smart marketing and are very fragile in the hands of greedy marketers. Overdoing marketing in this product category might remove the brand from the category suitable for the self esteem appeal.

Cognitive Needs – Splitting cognitive needs into aesthetic and information needs is appropriate for its marketing application. Works of art, designer products and jewellery are the best examples of products that address peoples’ aesthetic needs. Travel agencies offer holidays to places considered as beautiful to appeal to the aesthetic needs. The need for information on the other hand motivates us to buy information products such as newspapers, subscribe to a website or pay for a university course. Using the socio-economic classification of people, such as the one currently in use in the UK, can help the marketers to more accurately target consumers with products or services designed to attract people with an elevated high need for information.

Self-actualisation – Is the need to become more and more of what one is and to achieve everything one is capable to achieve. Targeting products which address the self-actualisation needs is difficult and expensive as it requires a thorough and detailed understanding of consumers’ personality and motives. Marketers can use projective research techniques to stablish the self-actualisation needs of an individual. People self-actualise in various different ways so finding a typical example of a product in this category is difficult. Some people climb Mount Everest while others grow their own food to self-actualise.

Reference

- Maciejovsky, B., 2012. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, Consumer Behaviour. Imperial College London, unpublished.

Written by Michael Pawlicki

Motivation

Motive is a reason for carrying out a particular behaviour. Motives are not instincts (pre-programmed, inborn responses). Needs are the basis of all motivation.

Motives can be subdivided into 6 motivational categories:

Primary motives – Replacement of a used product for a new one e.g. the purchase of a new car to replace an old broken one. The primary motive is a utilitarian one. A consumer purchases a new product because the one they already own no longer does what is intended to.

Secondary motives – Here the motive is more than just a utilitarian one. Unlike the primary, the secondary motives lead the consumer to buy into a specific brand. A product from a specific brand usually carries intangible benefits such as social image in addition to the service it performs.

Rational motives – Are based on reasoning or logical assessment. Rational motives are tradeoffs between the price the consumer has to pay for the product or service and the value it represents to this consumer.

Emotional motives – Having to do with feelings about the brand. Emotional motives are irrational. Consumers are motivated to but a product not by its utilitarian features or its market value but how they feel about it. Emotionally motivated purchases can usually be characterised as products or services of high cost to profit ratio (Good business for companies).

Conscious motives – Are the motives we are aware of and these can be both primary and secondary. People might or might not know what motivates them to buy a specific brand. Buying a luxury suit motivated by the need to look like peers at the workplace is very conscious choice of product.

Dormant motives – Operate below the conscious level. Buying a luxury suit can also be motivated by dormant motives such as appearing to the public as someone who you are not. Here the motive is derived from the discrepancy between the purchaser’s self-image and how others perceive this person. The purchaser is aware of the fashion standards of a social class they aspire to belong to but are not aware that they don’t belong to this social class. Companies, luxury brands in particular, base their marketing strategies on dormant motives by creating imaginary high social class role models for their customers to follow.

Reference

- Maciejovsky, B., 2012. Motivation, Consumer Behaviour. Imperial College London, unpublished.

Written by Michael Pawlicki